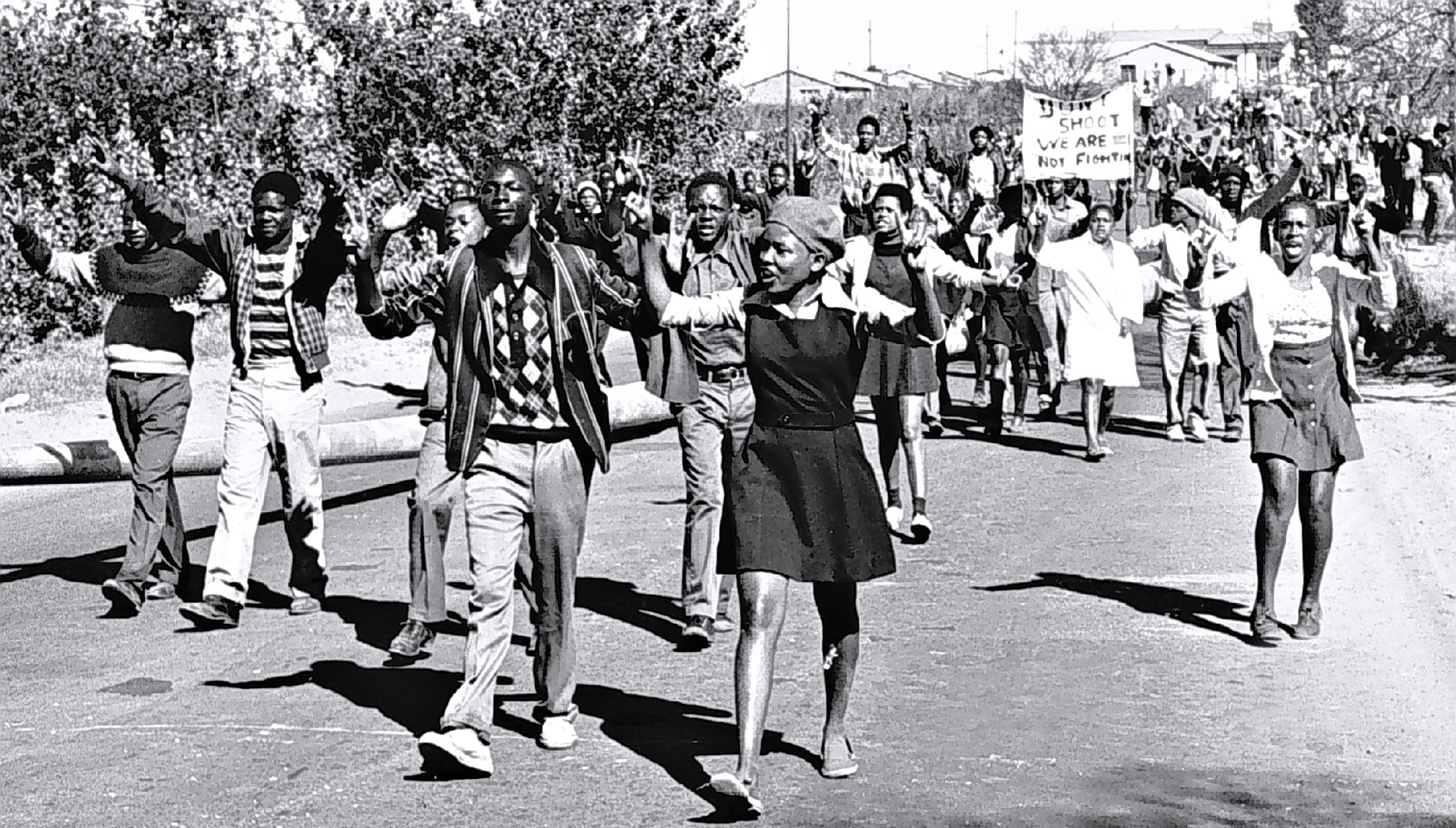

Image courtesy SA History Online

In 1976 the students at Morris Isaacson High School and many others in Soweto rose up to challenge the might of the apartheid state. They rose up against the introduction of Afrikaans as a medium of instruction at African secondary schools. This was at the peak of the Black Consciousness Movement (BCM), from the struggles that started with the emergence of the South African Students Organisation (SASO) in 1968 – led by Steve Biko, Barney Pityana and others – the Black People’s Convention (BPC) in 1972 and the South African Students Movement, which many in the 16 June 1976 leadership were members of. The state arrested the SASO/BPC leadership after they called rallies in solidarity with Frelimo in September 1974, convicting Saths Cooper, Muntu Myeza, Patrick ‘Terror’ Lekota, Aubrey Nchaupe Mokoape, Pandelani Nefolovhodwe, Nkwenkwe Nkomo, Kaborone Sedibe, Zithulele Cindi and Strini Moodley in December 1976.

At the first democratic general elections in South Africa in April 1994, nearly two decades after the 16 June 1976 uprising, the class of 1976 and the BCM were scattered across the political spectrum of South Africa. The majority had joined the African National Congress and the South African Communist Party in droves. Some had joined the Pan-Africanist Congress, while others remained in the Azanian People’s Organisation and a few other BCM structures. The students’ body that had organised itself in opposition to the introduction of Afrikaans as the medium of instruction was spread and was scattered among the political parties of South Africa. There was no central focus or command.

The focus of the 1976 students and BCM had been on establishing a one-person-one- vote of equal value for all adults of South Africa, enabling all to directly elect their political representatives as members of parliament and provincial councillors, in the same way that had existed previously exclusively for whites. We fought for equal rights for all the citizens of South Africa, black and white.

Yet the goal for establishing equal rights for all the citizens has remained elusive till today. The class of 1976 lost the ball and the focus. We have not reached the minimum goals of the BCM. One person one vote of equal value for electing our leaders remains elusive. We still do not have the same rights the whites had under apartheid. We have not yet reached Uhuru, as the Kenyan author, Ngugi wa Thiongo, would say.

The initial parliamentary electoral laws adopted for the first non-racial general elections in 1994 were understood to be temporary and not permanent, but they have been kept by subsequent ANC governments for three decades despite several proposals to change them.

In 1999 Electoral Task Team, chaired by Dr Frederick Van Zyl Slabbert, was instituted to explore alternative parliamentary electoral laws for South Africa. The Electoral Task Team presented its report to the Cabinet in March 2003 with two main recommendations: the minority recommendations and the majority recommendations.

The minority recommendations proposed continuation of the 100% proportional representation electoral system that was used in 1994, also known as a “closed list system”, for the National Assembly and provincial councils. In this system, citizens are only allowed to vote for political parties. The citizens have no rights to choose their representatives by name as individuals, they cannot choose members of parliament or provincial councillors. They cannot as voters choose their own representatives, in their own constituencies; they cannot de-select and reject for office any political representative who fails them. In this system, they cannot choose the president, they cannot choose the provincial premiers, and, at local level, their mayors. All these politicians are appointed by the political parties without the participation and inputs of the citizens. South African citizens are treated like children, with no right to choose for themselves who they want to represent them, and who are accountable to them in a constituency that they are responsible for.

By contrast, the majority recommendations of 2003 proposed that 75% (300) of members of parliament (MPs) should be elected as individuals in large, multi-member constituencies, with 25% (100) MPs being appointed in a proportional representation manner in a similar way to the current system. This majority recommendations were rejected by President Thabo Mbeki’s government, and has been continued by all subsequent ANC governments in the last twenty years.

Addressing the Kgalema Motlanthe Foundation Inclusive Growth Forum at a conference in the Drakensberg In October 2022, the former president of South Africa and ANC deputy president, Kgalema Motlanthe, said South Africa was on the brink of a precipice.

Former deputy finance minister, Mcebisi Jonas, said: “We need a fundamental rethink of the electoral system that has created a crisis of political accountability. I do not see how elected representatives will change their tendency to kowtow to the whims of their political parties unless the system changes to make them more accountable to their constituents.

“Any agenda for change must incorporate a mass mobilisation campaign for electoral reform, and we must all intensify the efforts by civil society organisations campaigning for a more constituency-based system of government,” he said.

These proposals were not supported by the ANC government. The ANC was no longer a party of reforms, as it was during the apartheid era, pre-1994. In power, the ANC became a party of retardation and regression. Most South African citizens have acknowledged that the rampant corruption is partly because of the lack of individual accountability of politicians to the voters. The class of 1976 has been swallowed by political events in South Africa and has lost focus on the original goals of the BCM to establish one-person-one-vote of equal value for all the citizens.

In 2020 the New Nation Movement took the Electoral Act to the Constitutional Court stating that the Electoral Act of 1996 was unconstitutional as it did not allow citizens without party affiliation and membership to stand for elections to parliament in national and provincial assemblies. It argued that the Electoral Act was prejudiced against ordinary citizens in favour of political parties by banning independent candidates, and that there was no justification for the limitation.

The National Assembly instructed the Minister of Home Affairs, Dr Aaron Motsoaledi, to facilitate the changes and amendments. He established the Ministerial Advisory Committee (MAC) chaired by former minister, Valli Moosa, to work on reforming the parliamentary electoral laws and amend the Electoral Act of 1996.

MAC produced two proposals. The minority recommendations proposed that 50% (200) members of parliament should be elected by allowing independent candidates to compete alongside political party candidates. The other 50% (200) members of parliament would be contested by political parties only. The logistics of implementing these reforms were not easy, as they required changes in the number of signatures for registration of political parties and for independent candidates to be revised. All in all, this is a partial reform from the 100% (400) MPs under proportional representation to 50% (200) proportional representation.

The majority report proposed a single-member constituency option which favoured introducing single-member constituencies, proportionality secured via party lists. In this case independents would stand as individuals in constituencies and compete together with those on party-lists.

After ignoring most of the public recommendations made, the past parliament, made up of conflicted MPs who owed their positions to their political parties, not the public, came up with an entirely unsatisfactory system that allowed “independent candidates” to contest against well-funded and organised parties in the elections on 29 May this year. Not one so-called independent made it as an MP! None will in future, unless the party-funding and electoral laws are seriously reviewed.

The 70s Group believes that the majority of MPs must be directly elected by the citizens, in a an accountable constituency-based system. Similarly, the president, premiers (if we need such provinces), and mayors should be directly elected by the citizens. This is the only way to establish accountability of politicians in South Africa, and make their oath of office meaningful.

The class of 1976 and the BCM still has a long way to go before realising true democracy in South Africa. We must continue campaigning for further parliamentary electoral reforms until individual accountability of politicians is established. We still do not have the same rights the whites had under apartheid.